The Dark Side of UX Design — Part 1: How brands might be manipulating your choices

06 February, 2018

This article will be published in two parts.

The first part will be a small historic revision of how propaganda paradigms went from the rational choice for a needed and useful product to the emotional appeal to consumer’s subconscious. And, of course, how these new paradigms were incorporated into Design, especially what we call today User Experience. To guide my thoughts, I’ll base myself on a BBC Documentary called The Century of the Self (Adam Curtis, 2002) (1).

The second part of the article will be a study with real life examples of manipulative and purposely confusing design patterns used to trick the user into taking the most beneficial decision for the business, in spite of the user’s best interest. Those are the UX Design Dark Patterns.

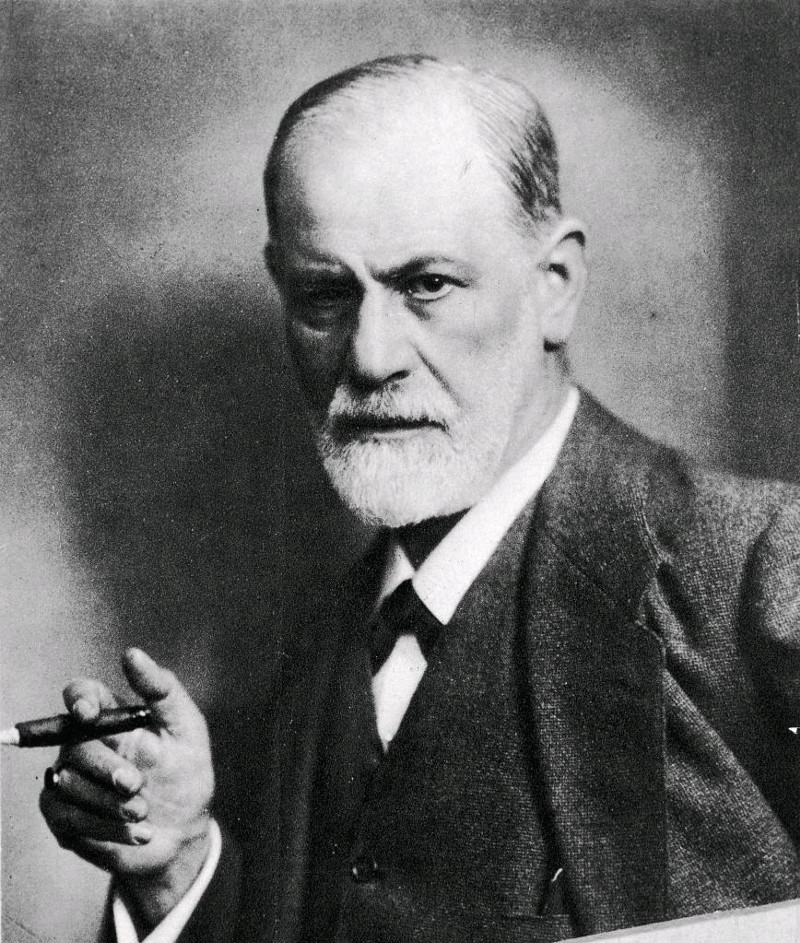

Freud can explain

Curiously, our story today begins with Sigmund Freud. In his studies about how our minds work, Freud identified that human beings are run by irrational desires that are repressed during our childhood and become part of our subconscious. Although this is an oversimplified way to put it — I’m not going to pretend to be a psychoanalysis specialist — , this means there are more factors in play when it comes to the mind’s decision process than merely the conscious reasoning.

One of the most prominent people of the time to use Freud’s ideas was his own nephew who lived in the United States, Edward Bernays. Bernays became known as the “father of public relations” and, believe me, this informal title wasn’t given in vain. Combining his uncle’s ideas with studies of Gustave Le Bon (2) and Wilfred Trotter (3), he understood that the repressed desires in the human subconscious could be dangerous and lead to a savage society, if not properly controlled. In other words, he considered the population irrational and prone to an erratic herd behavior (4). Due to this perception, he believed that the best option was to manipulate people so they would follow the “right path”.

In his professional life, Bernays was responsible for introducing in the American industry the idea that a product is more than its practical function. He associated sensations and emotions to his clients’ (big companies) products so they would trigger consumers’ repressed or unconscious desires. This was the beginning of the era of consumerism, where one sold the idea that a product could make you feel better, more special and more apt to express your personality to the world.

One of Bernays’ most iconic campaigns was the breaking of the taboo that existed over women smoking in public, in the beginning of the twentieth century. Sought by the American Tobacco Company, he accepted the mission of helping the cigarette industry to expand its market and absorb the female public. With help from the psychoanalyst A. A. Brill, Bernays planned the propaganda action that would take advantage of the feminist fight of the time, which fought for equality between men and women. But how could he accomplish something like that?

He hired women to go to the Easter Sunday Parade in New York City and smoke cigarettes in public. He also hired photographers to guarantee those women would be caught on camera. Through one of the women, he left the following message: “Women! Light another torch of freedom! Fight another sex taboo!”. The campaign message spread quickly and the act of smoking in public went from an undesired taboo to a representation of a powerful woman that fight for her rights. Cigarette consumption by women, which was 5% in 1923, doubled in a few years and finally culminated in 33.3% by 1965.

Bernays’ success in his campaigns — which included help to promote and elect politicians — changed completely the way products were presented to consumers. He even masterminded the new industry approach of selling product variations for different “groups” (punks, intellectuals, preppies, etc.) who started showing their personality based on the products they consumed. The marketing model that appeals to emotions and to human “weaknesses” became the new pattern. And, consequently, that pattern reflected how things were to be done in product design.

Selling Snake Oil

When it comes to designers, we know it by heart that a good design encompasses functionality — the form of the product must allow it to solve a problem — , interaction — the easiness for understanding how to use the product — , and experience — how that product makes you feel when you use it. The first two components are directly connected to the product’s usefulness, that is, to the purely rational reason why you would buy it. As for the third component (UX), although I consider it extremely important and use it every day as a designer, it can open the path to darker possibilities.

Experience Design: The practice of designing products, processes, services, events and environments with a focus placed on the quality and enjoyment of the total experience. — Don Norman, The Design of Everyday Things (2013)

UX it’s the part of Design responsible for proportioning good experiences, but what does that really mean? If I use a website or a product with a good interaction design, with pleasant aesthetics and that fills my needs in that moment without making me feel that I’m paying more than what my need is worth; to me, that will have been a genuinely good experience. But what if I get into a website that tells me the product I want is only available for a limited time — without it being true — and shows me a big fat chronometer displaying how much time I have left if I want to purchase? Also, this second site gives me almost no concrete benefit of the product and instead shows me pictures, from which 90% of them are of happy and handsome people using the product (but with no close-ups on the actual product). In this case, I can buy the product and feel happy and consider this a good experience because I was able to seize the opportunity, but will it have been genuinely good? With a combination of well-thought design and copywriting, here’s what happened:

- I felt a sense of urgency to make the decision of buying due to the use of the chronometer.

- I associated that product to happiness because I identified myself with the people in the pictures and, unconsciously, I wanted to feel like them.

- As a consequence, a product which was a merely interesting possibility became something “obviously beneficial” and I concluded the purchase.

Don’t get me wrong, I know the importance of good marketing to a business’ success and I see nothing wrong with promoting the product to make it easier for the interested client that is stuck on his own inertia to move towards buying. Nevertheless, I always like to question myself about where is the line that divides marketing (the good type of convincing) and manipulation. Taking the case I described above, for example, imagine the following changes:

- The sense of urgency could exist if, in fact, the sale was to end after a period of time. If the sale was continuous, eventual discounts valid for a limited time could create a more honest urgency. In both cases, the chronometer could be omitted or have its hierarchical importance diminished to avoid the pressure over the client.

- The pictures could be more balanced between pictures of the product in use and close-ups from different angles showing the product’s details and how it really is — after all, it’s the product I’m buying, not the happy family. Besides, the concrete benefits should be written in a very clear way.

In this little mental exercise, we could note that the first scenario — the one without these last changes I purposed — aims to exploit unconscious emotions and instincts so it can make the buyer give less attention to the real characteristics of the product and be defeated by consumerism. The second scenario still has an emotional appeal, but in a way that balances emotion with the rational inputs for the buying decision. In other words, the first scenario is prepared to sell snake oil, while the second is confident that its product has real value so it doesn’t need to hide it behind tricks.

Many other techniques can be used to achieve similar objectives to the one I described for the first scenario, but here we’re still talking about copywriting and marketing accompanied by design elements to increase conversion. They are practices that can be considered fishy or only a more aggressive way of doing marketing; it will depend on the specific situation and on who is judging.

When Design Goes to the Dark Side

Now, we’re going to go a little deeper in the participation of design elements in this context of user manipulation and we’ll finally get to the dark patterns (5).

A Dark Pattern is a user interface that has been carefully crafted to trick users into doing things, such as buying insurance with their purchase or signing up for recurring bills.

Definition from darkpatterns.org

When a dark pattern is used by a business, a choice is made for the short-term profit over providing real value and a good experience to the user.

Usually, these interfaces take advantage of the known fact that most of the time, people don’t stop to carefully read the information that is displayed on the screen. People scan, they don’t read. During this moment of lack of attention, the dark pattern creator hopes that you’ll make a decision that is not in your best interest because:

- You didn’t realize what you were doing;

- You realized just after making the decision and decided to let it go (you don’t want to lose more time; the effort to revert the decision is not worth it; etc.).

One common example of this type of pattern is the use of options checked by default that include you in a service, a newsletter or something similar. This options possibly don’t interest you, but they use it because the company’s metrics are showing an increase in conversion if the options are already checked — i.e., there’s more chance that the user will not notice it and just leave them checked.

Another example is the inclusion of products/services in your online shopping basket without you having ever selected them; normally, they will be things associated with the product you did choose. For instance, you choose to buy a tablet and the store automatically adds a case in your basket — and no, it’s not a gift. I’ll cover more examples like these in the second part of this article.

I know what you might be thinking: “oh, but a business has to do what it can to survive, times are rough and every tactic is valid to make sales increase”. Believe me, I know that pain. Selling is the most crucial part of having a business and the reduction of barriers of entrance for online businesses is making the environment increasingly competitive. But don’t dare to forget: companies only get to be successful in the long term if they provide a real value when selling and the exchange is good for both sides.

Imagine that a designer opts (or is told to opt) for the dark side and, with that, he increases conversion. The situation here has already evolved somewhat since the beginning of the consumerism era. Bernays got people to want to buy products they might not really need. Nowadays, dark patterns can make people buy without them noticing. Although the consumer manipulation mentality is the same, there’s a crucial difference: while in Bernays’ model people might never realize that propaganda is dictating their consumption habits; when design dark patterns are being used, people will eventually realize they made the purchase — even if it’s not until they have to pay their credit card. When this happens, three scenarios are probable:

- Clients will ask to cancel the purchase, adding frustration to the relationship between client and company and, still, the business will not get that payment.

- The business will make it extremely hard for the user to cancel the purchase. The person might give it up, but she’ll be two times more frustrated and very confident to give her negative impression of the company whenever possible — she might even decide to make negative advertising, initiate processes, etc.

- The person will let that payment go, either because it’s a very small amount or because she doesn’t want to lose the time. But she will feel betrayed and possibly never use the service again.

In other words, any business that worries about its financial health on the long run should avoid any of these design patterns that betray the user’s trust. There are a series of design and psychology techniques that can be used to optimize sales and don’t need to resort to fishy schemes. A good service/product that delivers a perceived value higher than its cost is still the best strategy to increase sales. Another approach is to use ethic and transparency in sales on your favor as marketing — show how you are different from the others because you have in mind your client’s interest. And, as a bonus, you’ll get a legion of people willing to make free propaganda for your company.

We could think, at a first glance, that the leaders in implementing design dark patterns would be small and medium businesses struggling to survive and resourcing to any sale strategy. That could not be further from the truth. The top cases of design being used in a purposefully confusing way are from BIG companies. Why do they act like that? I can only wonder about it having to do with over regulated markets where these businesses have practically no competition and, as a result, don’t need to worry about keeping customers happy.

What matters most here is this: the more we talk about and show the world about these techniques that exploit users, the more people will be conscious and able to recognize them before they become “victims”. And, at the same time, more designers can help spreading the message that there must be a limit in planning the interface and the UX to orient — or is it to manipulate? — the user’s actions.

References:

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Century_of_the_Self

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Le_Bon

(3) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilfred_Trotter

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herd_behavior