Usability in Bitcoin: BIPs

10 March, 2018

In the first article of this series, I’ve presented the concepts of mental models and metaphors, as used in the field of Design, and how they could influence people’s understanding of certain aspects of Bitcoin. The accuracy of this understanding would, consequently, have an impact on Bitcoin’s usability because it defines whether people found it easy or not to use.

Now, my focus will shift from design concepts applied to Bitcoin to an element of the Bitcoin environment that has had an important role in improving the system so we could get to the current level of usability. I’m going to talk about BIPs.

BIPs (Bitcoin Improvement Proposals)

A Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP) is a design document for proposing changes to the Bitcoin protocol, as first introduced by the programmer Amir Taaki in 2011. This has been the main channel to officially proposing updates to the software since then, and anyone interested can submit one through the bitcoin-dev mailing list, where it will be discussed. Although many of the implemented BIPs to this day have resolved pure protocol issues, some had a very positive influence on Bitcoin’s usability. One can argue, of course, that any improvement in the protocol will result in an improvement for the users, which I agree. But I’m limiting my scope here to two examples where the consequences to usability come straight from the protocol change.

BIP 21

Image by BTC Keychain

Image by BTC Keychain

Proposed in 2012 by developers Nils Schneider and Matt Corallo, it adopts a URI scheme for making bitcoin payments. To make it clear, a URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) is a string of characters used to identify a resource and, in the case of Bitcoin, it meant the creation of a consistent syntax to identify payments in the Bitcoin network. The motivation, such as is stated in the BIP text, can talk for itself:

“The purpose of this URI scheme is to enable users to easily make payments by simply clicking links on web pages or scanning QR Codes.” (1)

As simple as it may sound, this BIP was one of the greatest advances in terms of payment usability. It fits Bitcoin so well that most users probably don’t even realize this was an improvement and not a pattern established from the beginning. Here’s what I’m talking about:

Suppose you want to make a donation to a site that you opened in your notebook using your smartphone wallet app. Nowadays, this is as simple as pointing the phone’s camera and reading the QR code with the address you want to send money to. It might even already include the amount in the QR code information.

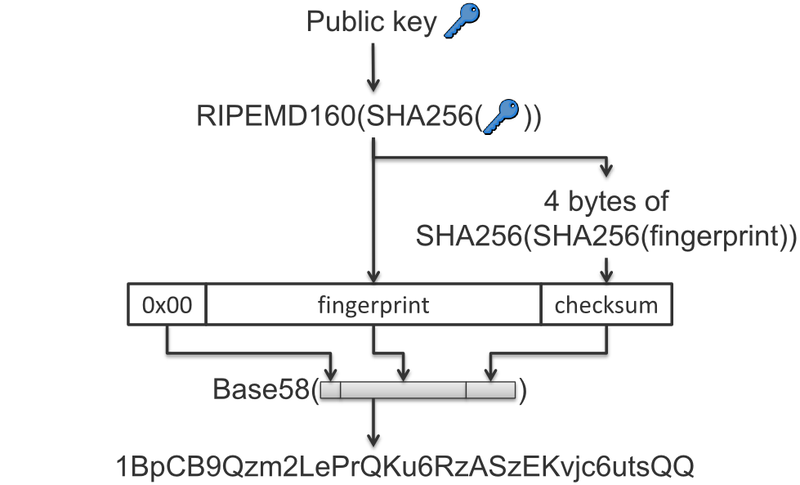

But, before BIP 21, you’d have to type in each character. It was a tedious and worrisome task where the user felt pressured not to make a mistake. It is true that most decent clients use the checksum for the address (see image below) to guarantee that you are sending money to a valid address, so you should be relatively safe even when typing. But since the worst case scenario is a total loss of funds, you don’t want to count one hundred percent on someone’s implementation or risk the “luck” of mistyping into a wrong but valid address. That’s why, even today, you’ll see services alerting you to avoid typing the address.

Formation of the Bitcoin address from the public key. It shows the 4 bytes used as a checksum to verify if the address is valid. — Image from the bitcoin wiki

Formation of the Bitcoin address from the public key. It shows the 4 bytes used as a checksum to verify if the address is valid. — Image from the bitcoin wiki

Apart from the direct security risk of sending money to the wrong place, didn’t I say it was a tedious task? This incurs in two interlinked problems: excessive cognitive load and degradation of the user experience.

“In the field of user experience, we use the following definition: the cognitive load imposed by a user interface is the amount of mental resource that is required to operate the system. Informally, you can think of mental resources as “brain power” — more formally, we’re talking about slots in working memory.” Kathryn Whitenton on Nielsen Norman Group (2)

A cognitive overload is likely to happen because you are trying to remember and reproduce a stash of letters and numbers with no particular meaning to you, i.e., perceptively random. This process will take up space in your working memory, the system responsible for managing incoming information and manipulating what is already stored, similar to a computer’s RAM. It has a limited capacity for dealing with information and it tires us to use this memory extensively (3). This will make it more likely that mistakes are made during some part of the copying — resulting in the frustrating need to repeat the process until you get it correct — or in the steps that follow — such as the amount or the fee being sent, for example.

What I’ve just described will have the inevitable outcome of degrading the user experience or, put simply, it will make the user feel bad. This could be triggered by:

- Boredom related to the extensive copying.

- Fear of sending money to an incorrect address.

- Getting tired of paying attention to the address numbers and letters.

- The frustration of realizing there was a mistake in the process.

All of these risks and unwanted factors are almost completely avoided with the introduction and proper usage of BIP 21.

BIP 32 and BIP 39

BIP 32 (4) was authored by Pieter Wuille and it describes the creation of hierarchical deterministic wallets (or HD wallets, for short), which are wallets that can be shared partially or entirely with other systems. As for BIP 39 (5) , it was written by the collective: Marek Palatinus, Pavol Rusnak, Aaron Voisine and Sean Bowe. It describes the implementation of a mnemonic code, i.e, a group of words that are relatively easy to remember, for the generation of the seed of HD wallets. Both of them are being described in this same section because their consequences are complementary in the improvement of a fundamental part of Bitcoin’s usage: backing up your wallet. To put them under the desired usability perception, I’ll start by describing how the backup process occurred before them.

Each wallet generated a pool of addresses in a pseudorandom (6) way so they could be used. The user should backup the wallet so he would not lose his money in case something happened to the computer/device (it’s the same logic of backing up your photos and files). As the addresses were used, that number of available addresses was exhausted — since we avoid reusing addresses for privacy reasons — and the wallet generated a new batch of addresses. This meant that the user needed to make new backups from time to time, instead of making it only once because, if new addresses were generated and were not in the last backup, those funds wouldn’t be recoverable.

BIP 32 proposes a solution to this problem with the Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) wallets, where deterministic is the opposite of random. When using this BIP, wallet clients would be able to depend on a single root (a master key pair) to generate as many addresses as were necessary. The wallet backup could be made only once — when starting the wallet for the first time, for example — because this backup would hold, in reality, the master keys that can generate all the other. That removed a burden translated as the cognitive load on the user who needed to constantly think about and check if his backup was updated. Not to mention that backing up is a laborious process if it is to be done in the safest possible way. Which also means that, by removing the regular backup, we also remove great chances of mistakes during the procedure, such as skipping steps, committing security flaws and writing down the wrong information.

As for BIP 39, it works as a complement to the former BIP because it implements the mnemonic code generation that can be used to produce the master key pair of the HD wallet. The code is composed of a list of common words that should be chosen randomly. As it is perfectly stated in the BIP documentation, this code is better for human interaction than the alternative — i.e., you can read it more easily than the numeric representations of a wallet seed. That’s another huge reduction of cognitive load because, instead of copying random numbers, you are able to recognize a small word in a blink of an eye and that recognition allows you to remember it easily when you are transcribing from your backup to the wallet client — I’m assuming here the common case where the mnemonic is stored in a separate place from your device, such as a piece of paper.

To make it even more friendly, the wallet client can take advantage of the words used in the code being part of a known closed list. Thus, the software can assist the writing process by offering suggestions to autocomplete the words, avoiding any mistyping that would lead to an invalid seed. What you get here as a user, is the tranquility of quickly writing the words and going for the proper suggestion without having to worry about spelling or about the word not being on the mnemonic list. This “tranquility” can be expressed, in official terms, as the lack of pressure in writing with the right grammar and as a small assurance that the backup process was done correctly when the expected word appears as a suggestion by the client (a perfectly timed feedback). Both improve the experience of recovering a backup for the person.

In a nutshell, your backup can now be as simple as a list of words on a paper sheet. You can check out BIP39 in practice here on this page and here’s an example of the BIPs in action:

Mnemonic code:

audit order axis abuse artefact noise chapter join surface unit inflict smart bicycle sponsor have

BIP seed:

9c7bf26284df682ab621b82fb84d9cd25131eb92070b38de051ca67ff43013bb980ef10076c93b36d68c308aaae1327b12c33b24ae9634391ed927ebedaf2fe1

BIP root key:

xprv9s21ZrQH143K3FKe2cTQY8muB1jmE1TvM5MNU2aTDDqaVUSUVZCzEw6K124gEi9qiSkDQhsvmXpeYmAoU4t3P7powcKSy4bs6HPP8n11F97

Note: The above data was generated in Ian Coleman’s page with the implementation of BIP 39 just as an example to illustrate the previous discussion. It’s not secure to use it for storing your bitcoins.

The BIP seed is what allows you to create a single backup that will be able to recover all your keys, no matter how many new addresses you generated. And the mnemonic code is what you need to write down (or store in some other way), instead of having to keep the huge number of the BIP seed.

Conclusion

With these considerations, I hope to have made it clearer how protocol improvements can have a direct impact in Bitcoin’s usability, even though it’s not normally thought to be a top priority matter in the development of a high risk and security critical system, such as this one. It can even be said, based on the words used by the developers themselves when proposing the changes, that there’s a conscious effort to make it easier for people to use the currency. “Making it easy”, after all, is another way to say the system is more secure, due to the consequent protection of the user against his own mistakes.

References:

(1) https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0021.mediawiki

(2) https://www.nngroup.com/articles/minimize-cognitive-load/

(3) https://www.nngroup.com/articles/minimize-cognitive-load/

(4) https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0032.mediawiki

(5) https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0039.mediawiki

(6) https://engineering.mit.edu/engage/ask-an-engineer/can-a-computer-generate-a-truly-random-number/